The Seeds of Iniquity

How America's Justice System Became a Profitable Marketplace of Human Misery

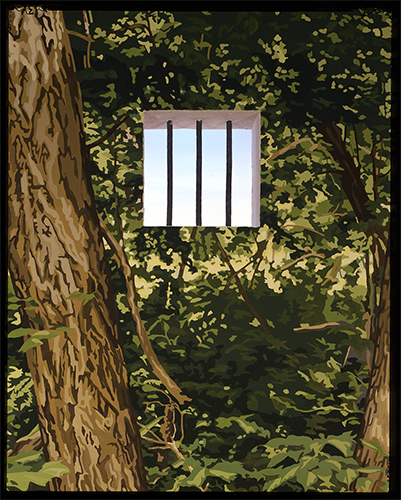

In the shadowed corners of American enterprise, where profit margins bloom in fields fertilized by human suffering, lies a system so meticulously engineered that its iniquity feels almost organic. The roots of this system burrow deep into the soil of private prisons, corporate exploitation, and a justice system designed not for rehabilitation, but for perpetual subjugation. These are not mere accidents of capitalism, nor unintended side effects of policy oversight. No, these are the carefully sown seeds of iniquity.

The Business of Incarceration: A Profitable Harvest

Private prisons have transformed punishment into profit, human beings into assets, and rehabilitation into an afterthought. The United States, home to 5% of the world's population but nearly 25% of its incarcerated individuals, serves as fertile ground for this industry. Companies like CoreCivic and GEO Group, two of the largest private prison operators, have built empires on contracts that guarantee high occupancy rates. Their profits hinge not on reducing crime, but on sustaining a steady flow of inmates—a flow disproportionately fed by marginalized communities (Source: The Sentencing Project, Criminal Justice Reform).

Conditions within prisons remain appalling. At notorious facilities such as Rikers Island, reports of abuse, medical neglect, and violence are routine. Since Mayor Eric Adams took office in January 2022, at least 33 individuals have died in New York City jails—a grim toll that serves as an indictment of a system left to fester (Source: Katal Center, AP News).

In March 2022, Herman Diaz choked to death on an orange at Rikers Island. Fellow inmates desperately attempted to save him while correction officers reportedly stood by, indifferent to his gasps for air (Source: The New York Times).

In May 2022, Emmanuel Sullivan was discovered dead in his bed at Rikers Island. Despite visible signs of medical distress, officers failed to perform adequate wellness checks (Source: NY1).

In June 2022, Anibal Carrasquillo died after complaining of chest pains. Officers ignored his pleas for help, allowing his condition to deteriorate until it was too late (Source: NY1).

In July 2022, Elijah Muhammad sustained severe injuries during an altercation with guards at Rikers Island. Surveillance footage revealed a shocking delay in calling for medical assistance, and Muhammad succumbed to his injuries hours later (Source: The New York Times).

In February 2023, Manuel Luna was found unresponsive in his Rikers Island cell. While the cause of death remains under investigation, early reports suggest gross medical neglect (Source: NY1).

In July 2023, Joshua Valles was reported dead under highly suspicious circumstances. Officials first claimed a heart attack, but an autopsy revealed a fractured skull, leaving unanswered questions about what really happened (Source: NY Daily News).

In December 2024, at Marcy Correctional Facility, Robert Brooks was viciously assaulted by correctional officers while handcuffed. Body camera footage captured the horrifying sequence of events—officers striking him repeatedly in the face and neck, ultimately causing asphyxia due to neck compression. He died the following day (Source: BBC).

Further, patterns of abuse have been uncovered at Marcy Correctional Facility, where lawsuits have documented recurring violence and misconduct by correctional officers. These patterns suggest a deeply entrenched culture of brutality and impunity within the institution (Source: CNY Central).

In addition to physical abuse, systemic sexual violence in New York correctional facilities has led to nearly 1,800 survivors filing lawsuits under New York's Adult Survivors Act. These lawsuits reveal a culture of exploitation and cover-ups, underscoring the urgent need for reform (Source: PR Newswire).

In response to the recent murder of a CEO, Governor Kathy Hochul boldly stepped forward to propose a dedicated safety hotline for New York's most marginalized group-insurance executives. No such service has been proposed for the incarcerated men and women who live under the constant threat of beatings, suffocation, and slow, preventable deaths.

Each of these deaths and abuses exposes the unchecked power of correctional officers and the dehumanizing conditions inmates endure. These facilities have become breeding grounds for violence and systemic failure, all while private prison companies continue to lobby for harsher sentencing laws that ensure a steady flow of incarcerated individuals.

Legalized Slavery: The 13th Amendment's Fine Print

While the 13th Amendment ostensibly abolished slavery, it left one glaring loophole: "except as a punishment for crime." This exception has allowed prison labor to persist under exploitative conditions. Inmates are often paid pennies per hour for laboring in factories, manufacturing goods, and even fighting wildfires. Many corporations, including McDonald’s have quietly benefited from this modern-day serfdom (Source: ACLU, AP News).

The irony is as bitter as it is blatant: the same corporations that profit from prison labor are often the ones lobbying for harsher sentencing laws, ensuring a steady supply of captive workers. CoreCivic and GEO Group have spent millions lobbying Congress to push for policies that favor mass incarceration (Source: OpenSecrets).

Rehabilitation and Second Chances: Lessons from Abroad

Norway

In stark contrast to the punitive approach in the United States, many European countries prioritize rehabilitation and reintegration. Norway, for example, maintains one of the lowest recidivism rates in the world, at approximately 20% within two years of release, compared to over 70% in the United States. Norwegian prisons focus on education, skill development, and mental health care, treating inmates as individuals capable of change (Source: World Economic Forum).

How did it become possible? In the 1990s, Norway had nearly the same recidivism rates as the US today. The prison system was built in a similar way: long sentences and a harsh environment—a message to others: you commit a crime, you get a severe punishment. Nevertheless, crime and recidivism rates were high. The Norwegian government recognized the problem and found a drastic solution: a complete overhaul of the prison system. But the biggest change wasn't the revamped formal structure—it was the new approach to prisoners and imprisonment. A prisoner is still a member of the society, a human being that is temporarily isolated from others, and that eventually will reenter this society. The focus is placed on maintaining ties to family and friends and facilitating reintegration after the punishment is over. In fact, Norwegian prisons offer a variety of courses and programs that help inmates preserve their competencies or acquire new skills. Recognizing the dignity of prisoners and treating them humanely, Norway ensures their mental and emotional well-being, thus increasing their chances of a better readjustment after release. Apart from social value, the country acknowledges the financial potential of incarcerated individuals—capable adults benefit the country’s economy. Numbers speak for themselves: individuals who were unemployed before prison experience a 40% increase in employment rates after their release. (Source: The Borgen Project)

A variety of research shows that long prison sentences don’t deter crime, neither is there any proof that the death penalty does so. The 1990s Norwegian criminal law reform also changed the way people are sentenced: the life sentence was abolished and replaced with a maximum sentence of 21 years, which was later extended to 30 years for crimes against humanity. Despite this, 90% of the sentences are less than a year long, with 60% of them being less than three months. (Sources: National Institute of Justice, Norwegian Correctional Service).

While the government provides the conditions for rehabilitation and reintegration, it is the collective belief in redeemability and personal value that makes them effectively possible.

Germany

Similarly to their Norwegian counterparts, the German authorities recognize rehabilitation and reintegration as the objectives of incarceration. The limitation of individual’s liberty is a punishment in itself—there is no need to humiliate or torture a person—the goal is to re-educate and prepare for a return to normal life. The U.S. incarceration rate is roughly nine times higher than that in Germany, where most people receive community-based sanctions, such as day fines or community service. In case of conviction, German sentences tend to be significantly shorter than those in the U.S.: the overwhelming majority are suspended with only about 5% of adults serving time in actual prisons. Most of the prison sentences are under 12 months, with about 30% being less than 6 months. The death penalty and life without the possibility of parole do not exist in Germany (Sources: Fair and Just Prosecution, Federal Ministry of Justice).

The humanistic approach is also evident in the alternatives to the real prison sentence. For example, day fines are calculated based on the seriousness of the offense and the person’s ability to pay—there is a possibility to pay them in installments or replace with community service instead.

The goal to rehabilitate and re-educate inmates is pursued at the individual, institutional, and physical levels. Prisoners are allowed to wear their own clothes, prepare their own food and keep their belongings. On an institutional level, corrections staff have to undergo specialized trainings, that are similar to those of social workers in the U.S. The training lasts two years during which future corrections officers study such subjects as psychology, conflict management, communication with prisoners. In German prisons, the emphasis is put on positive reinforcement and forming a relationship of trust with inmates. Disciplinary measures such as solitary confinement are used as a last resort and for a very brief period of time: the German law limits the use of solitary confinement to a maximum of 4 weeks per year (Source: Vera Institute of Justice).

On the physical level, prison facilities are designed to bolster rehabilitation: prison cells resemble dormitories, with openable windows, furniture, and amenities.

The Netherlands

A similar approach to incarceration in the Netherlands led to prisons being converted into schools, hotels and refugee centers—the country’s incarceration rate is about 65 prisoners per 100,000 population compared to 614 in the United States. (Source: Prison Policy Initiative)

The Nazi occupation left a lasting impression on the Dutch mentality—the Netherlands had “a strong sense of the dangers of an overbearing state and the horrors of imprisonment”, explains Francis Pakes, a Dutch national and professor of criminology at the University of Portsmouth. The Dutch government found the alternative methods to be more effective. Beginning in 2006, the prosecution was given the opportunity to settle some cases without the involvement of a judge—by using non-custodial sentences such as curfew, community service or fines. This approach combined with programs that emphasize vocational training and social reintegration, preparing inmates for life after prison rather than setting them up for inevitable failure, permitted to bring down crime rates and to close dozens of prisons (Source: Positive News).

The Financial Web: Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street

The influence of financial giants like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street extends far beyond Wall Street. These asset management behemoths hold substantial investments in private prison companies. BlackRock is the largest investor in CoreCivic, with a stake of 15.38%, while Vanguard holds approximately 12% and State Street around 8% (Source: Business of Business).

This financial entanglement creates a cycle where profits from mass incarceration flow back into the portfolios of institutional investors, perpetuating the system at every level. It is a web of complicity, one where economic power reinforces social injustice.

Reaping What We Sow

The American prison system is not broken; it is functioning exactly as intended—as a profit-generating engine fueled by human suffering. Every element, from punitive sentencing laws to privatized facilities, serves a singular goal: maximizing returns for investors at the expense of society's most vulnerable. We have built a world where a human being's freedom is a tradable commodity, and their suffering is just a line item on a quarterly report.

This isn't just a moral failure; it's a catastrophic societal one. Every dollar earned through these systems is stained with exploitation, and every moment we allow these cycles to continue pushes us further from justice and humanity.

The seeds of iniquity have grown into forests of injustice, their roots entwined in every corner of our institutions. The question is no longer whether we can afford to dismantle these systems, but whether we can afford not to.

Fyodor Dostoevsky once said, “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons”—so what can one say about our society? The choice remains ours, but every moment we hesitate, the clock is ticking—and the hour is growing late.

In collaboration with SLSGS.