It’s been five years since the world was rocked by COVID-19. The lockdown seems like a distant memory, and yet sometimes I catch myself thinking about how we were going crazy being locked up in our homes. I can stay home for a few days just because I don’t have to go anywhere, and it doesn’t bother me at all. But during the pandemic, it was different: the inability to go out of your own free will, the awareness that this choice had been taken away from you—this is what made it unbearable. That was the closest each of us has ever come to imprisonment. But have you ever thought about what actually happens behind prison doors?

Inmates' routines are strictly controlled; even minor infractions, such as having an untucked shirt, can lead to disciplinary measures. The disciplinary measures vary from losing the privilege to send and receive mail or make phone calls to being sent to the Special Housing Unit (SHU), also known as ‘the hole’ or ‘the box.’ Originally intended as an extreme punitive measure, today the SHU is used as a control strategy in many prisons. Some groups of people are especially vulnerable to this practice: statistics show that an overwhelming majority of inmates placed in solitary confinement are people of color (Sources: Michigan Journal of Race & Law; Atlantic Journal of Communication). Minors, LGBTQ individuals, inmates deemed at risk of victimization—they are often placed in isolation for their own protection, but does it actually protect them? It’s extremely difficult to conduct proper research in prison conditions, which contributes to diminishing the real scale of the phenomenon. Nevertheless, the available data is shocking. There are virtually no adequate criteria for placing transgender people in prisons: many facilities use sex assigned at birth and similar practices, increasing their vulnerability to abuse. (Sources: National Center for Transgender Equality; Prison Policy Initiative). Being segregated from the general population also means being alone with prison staff—the only people who connect you to the world. This already disproportionate power gap increases even more. The absence of a defined system of checks and balances within the prison leaves you at the mercy of correctional staff, which often leads to horrendous abuse of power. Many LGBTQ people report cases of sexual assault at the hands of prison personnel. (Sources: PREA Resource Center; Solitary Watch).

“I remember, he punched me so hard in my ribs, that I could barely breathe… he hit me so hard that I grabbed myself on the bed and that’s when he came behind me and he was grabbing me, choking me and hitting me, pinning me down… there was a point I couldn’t even move.”

If you think that solitary confinement is limited exclusively to the prison environment, you are terribly wrong. Recent events have drawn a lot of criticism to ICE practices, but the truth is, its modus operandi is not much different from what it has always been. People in immigration centers are a vulnerable category per se: they can’t afford legal representation, don’t know the laws, and often don’t even speak English—all of which makes them an easy target. It doesn’t take much to be sent to solitary confinement: sometimes, having an extra blanket, leaning back on chairs, translating for a non-English-speaking detainee, or complaining about the quality of the drinking water is enough (Sources: National Immigrant Justice Center). These are men, women, children, elderly, and disabled people whose only crime is crossing the border—often while escaping danger or death.

“If I spoke too loudly, solitary. If I climbed on top of a table to get a guard’s attention, solitary. If I had suicidal thoughts, solitary. When the guards would tease me about being deported back to my home country and make airplane sounds at me and gesture like a plane was taking me away, I would become upset and then get solitary for being upset.”

“[T]he lieutenant came and told me that I had to sleep in the top bunk bed or else I would go to solitary confinement. The lieutenant told me to get a medical reason for not being able to sleep in the top bunk bed. I told him the reason was in the medical records, and he told me he would not review anything to prove the medical reason. I was forced to sleep in the top bunk bed, and I could not get down until my dorm roommates got me down. I missed most of the meals on Sunday. On Tuesday, I [requested] another medical report that stated that I could not sleep in the top bunk bed.”

Why do people do this to other people? Well, let’s take a look at the famous Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE). In 1971, Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo and his team recruited 24 psychologically healthy young men. Half of them were assigned the role of prisoners, while the other half were assigned the role of guards. A prison environment was recreated in the basement of Stanford’s psychology building: three cells designed to house three prisoners each, a prison yard, and a closet for solitary confinement. The experiment was supposed to last two weeks, but Zimbardo had to stop it after only six days. The guards became extremely cruel and aggressive, while the prisoners became apathetic and submissive. The experiment revealed how easily people are influenced by their social roles.

A decade before the SPE, Stanley Milgram conducted another experiment. Participants (the 'teachers') were instructed by an experimenter to administer electric shocks to another person (the 'learner') for every wrong answer the learner gave, increasing the intensity of the shocks after every mistake. The electric shocks were not real, but the results were very much real: all participants went up to 300 volts, with 65% of them delivering shocks at 450 volts. The Milgram experiment revealed that people are more likely to follow orders if they come from an authority figure, even if those orders contradict their own principles. Additionally, people are more willing to cause physical harm to another person if responsibility is passed on to someone else (the authority).

Craig Haney, an American psychologist, has been studying prison isolation and the psychological effects of incarceration. He was part of the SPE team and conducted extensive research on Supermax prisons. In 2012, Haney testified as an expert witness before the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Human Rights of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary at a hearing titled 'Reassessing Solitary Confinement.' (Source: US Senate Committee on the Judiciary Disclaimer: the testimony contains graphic descriptions). Here’s his description of life in the SHU:

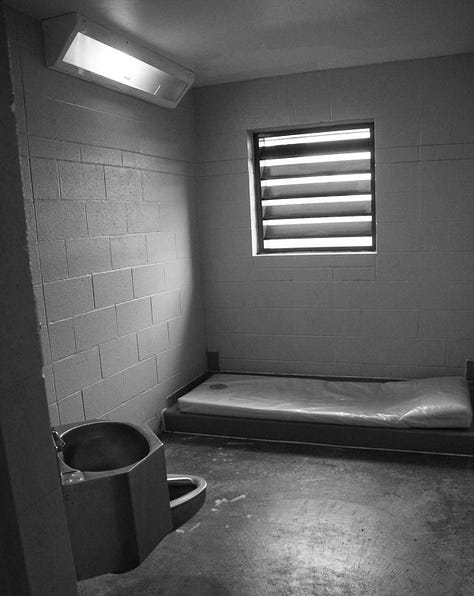

“[Prisoners] are confined on average 23 hours a day in typically windowless or nearly windowless cells that commonly range in dimension from 60 to 80 square feet. The ones on the smaller side of this range are roughly the size of a king-sized bed, one that contains a bunk, a toilet and sink, and all of the prisoner’s worldly possessions. Thus, prisoners in solitary confinement sleep, eat, and defecate in their cells, in spaces that are no more than a few feet apart from one another.”

“Reflect for a moment on what a small space that is not much larger than a king-sized bed looks, smells, and feels like when someone has lived in it for 23 hours a day, day after day, for years on end. Property is strewn around, stored in whatever makeshift way possible, clothes and bedding soiled from recent use sit in one or another corner or on the floor, the residue of recent meals (that are eaten within a few feet of an open toilet) here and there, on the floor, bunk, or elsewhere in the cell. Ventilation is often substandard in these units, so that odors linger, and the air is sometimes heavy and dank. In some isolation units, prisoners are given only small amounts of cleaning materials—a Dixie cup or so of cleanser—once a week, making the cells especially difficult to keep clean.”

This is not a dramatic book description; this is a quote from an official court testimony, and for thousands of people, it’s an everyday reality that lasts for years. Living in such conditions leads to severe psychological and psychiatric disorders, including insomnia, anxiety, hallucinations, suicidal thoughts, self-mutilation, paranoia, psychosis, and various cognitive dysfunctions. I will not include graphic descriptions in this article, but they do exist, and they are heartbreaking because behind each of them is a living, breathing, and broken human being.

Another important problem with solitary confinement is the inability of prisoners to return to normal social life after prolonged isolation. There is virtually no integration program in American prisons to help inmates readjust. Many are released from prison directly from the SHU—the leap from no human contact to a bustling social life causes immense stress and frustration for former prisoners, often leading to tragic consequences.

Solitary confinement does not end when the person leaves ‘the box’, it becomes part of them. Anthony Graves, who was wrongfully convicted and spent 10 years in isolation, said he still feels its effects:

“I haven't had a good night sleep since my release. I have mood swings that cause emotional breakdowns”.

Sarah Shourd spent 410 days in solitary confinement in Iran, she recalls her return to the United States like this:

“All I dreamt about in solitary was seeing my friends and family again, but in the early weeks after my return to the United States in 2010 I couldn’t look into another person’s eyes without physical discomfort. I had scars, but no one could see them. A touch on the shoulder made me flinch and tense up; I slowly began to reconstruct walls around me. A year later, I’d still wake up terrified in the middle of the night, feeling so alone. I’d lie still for hours, wishing I could disappear. It was in that darkness—that quiet—that I could no longer escape what felt like a hole carved out of my soul. Five years later the uncontrollable bursts of rage are gone, the depression and insomnia are mostly gone—but I still have to work hard sometimes to fill that emptiness, to restore my faith in humanity.”

While doing research on solitary confinement, I came across a book. The cover caught my eye: it is black, covered in scribbles, and in the center of it, there’s a person in an orange jumpsuit curled up in the fetal position—it is an instinctual way of coping with stress and anxiety. The cover transmitted the utmost feelings of despair and fear. Adults are supposed to be independent, they are supposed to protect children from the cruelties of this world. What is so scary that it makes an adult person retreat to their primary state? I opened the book and started to read. The preface alone made me cry. Here are two quotes from it:

“As long as you’re stuck in this coffin that silent scream becomes the backdrop of every moment of your waking life. It could last a month, a year, a decade, or the rest of your life, yet no one will ever hear it but you.”

“In solitary confinement, a grey, limitless ocean stretches out in front of and behind you—an emptiness and loneliness so all-encompassing it threatens to erase you. Whether you’re in that world a month, a year, or a decade, you experience the slow march of death. Day by day you lose your connection to everything outside the prison walls, everything you once knew and everything you once were.”

The book is called ‘Hell Is a Very Small Place: Voices from Solitary Confinement’. It’s a collection of testimonies from people who have been—or still are—in solitary confinement. No one can tell this story better than those who have experienced it firsthand. We live next to prisons, we pass them by on our way somewhere, we accepted them as a normal part of our everyday lives. Yet, rarely does someone ask themselves what it’s like to be incarcerated. We are taught from a very young age that bad people go to prison because they do bad things. We grow up and never really question this unless we come into direct contact with the matter. But the concept of imprisonment is not black and white; it has many shades and extends far beyond the prison itself. When you look into solitary confinement, you are looking into a dark abyss. It’s scary, it’s barbaric, it’s the antithesis of modern humanistic values—and yet, we allow it to exist when we choose to look the other way. For centuries, people have been pointing out the inhumane and pointless nature of social isolation. After visiting an American prison, Charles Dickens wrote:

“I believe that very few men are capable of estimating the immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment, prolonged for years, inflicts upon the sufferers; and in guessing at it myself, and in reasoning from what I have seen written upon their faces, and what to my certain knowledge they feel within, I am only the more convinced that there is a depth of terrible endurance which none but the sufferers themselves can fathom, and which no man has a right to inflict upon his fellow creature.

I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body; and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore the more I denounce it, as a secret punishment which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.”

The UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment defines the term ‘torture’ as follows (Source: The UN Convention against Torture):

“Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.”

The UN Nelson Mandela Rules say that solitary confinement of more than 15 consecutive days is considered a form of torture (Source: The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners). While different states have taken measures to limit solitary confinement, this cruel practice remains widespread (Sources: Brennan Center for Justice; US Government Accountability Office). Across U.S. state and federal prisons, on a given day, 122,840 people were locked in solitary confinement for 22 or more hours a day (Source: A Report by Solitary Watch and the Unlock the Box Campaign, May 2023). Moreover, various research consistently demonstrates that solitary confinement is not an effective tool of rehabilitation—on the contrary, it exacerbates aggression and recidivism, ultimately serving no constructive purpose. Instead, it breaks the human spirit and strips people of their basic dignity.

It is difficult to face the ugly truth, but it's necessary because it's the first step toward change. This is what I wanted to share with you in this article. While I have read hundreds of pages on the subject, I can only imagine what it's like for people who live this experience every day for months, years, or decades.

I asked a friend of mine about her thoughts during her brief arrest. Although she wasn't in solitary and spent just one day in custody, her description echoed what people in isolation describe: losing track of time, lacking natural light, being unable to see the sun, and feeling disoriented and scared. It made me realize that the psychological impact of confinement begins long before being placed in the SHU. If you're still skeptical about the severity of solitary confinement, consider this simple experiment: spend just 24 hours in your bathroom without any electronic devices, books, or ways to track time. Although this is surely a more comfortable version than what many people face, it may help you grasp the psychological challenges and disorienting effects of isolation.

I would like to leave the conclusion to Sarah Shourd:

“There are better ways to manage a prison than crushing inmates, treating them worse than animals, and driving them insane and then releasing them back into society. Locking a person in a box is a sick and perverse thing to do. It benefits no one—not even the governments who allow it. It’s torture.

Being human is relational, plain and simple. We exist in relationship to one another, to ideas, and to the world. It’s the most essential thing about us as a species: how we realize our potential as individuals and create meaningful lives.

Without that, we shrink. Day by day, we slowly die.”